Imagine holding your newborn infant and hearing from your pediatrician that your child has a malformation of his or her heart, known as congenital heart disease (CHD). About 40,000 parents in the United States will hear this news every year.

CHD is the most common birth defect that affects about 1 in 100 babies born each year. It occurs when the heart or blood vessels near the heart don’t develop normally long before birth. The defects can range from having a small hole in the heart to issues with the heart’s muscles to poor connections among the heart’s blood vessels.

While some infants with CHD do not exhibit any symptoms, others experience life-threatening conditions, such as heart failure, and some even succumb to the disease. In other cases, signs and symptoms of CHD may not appear until years after birth.

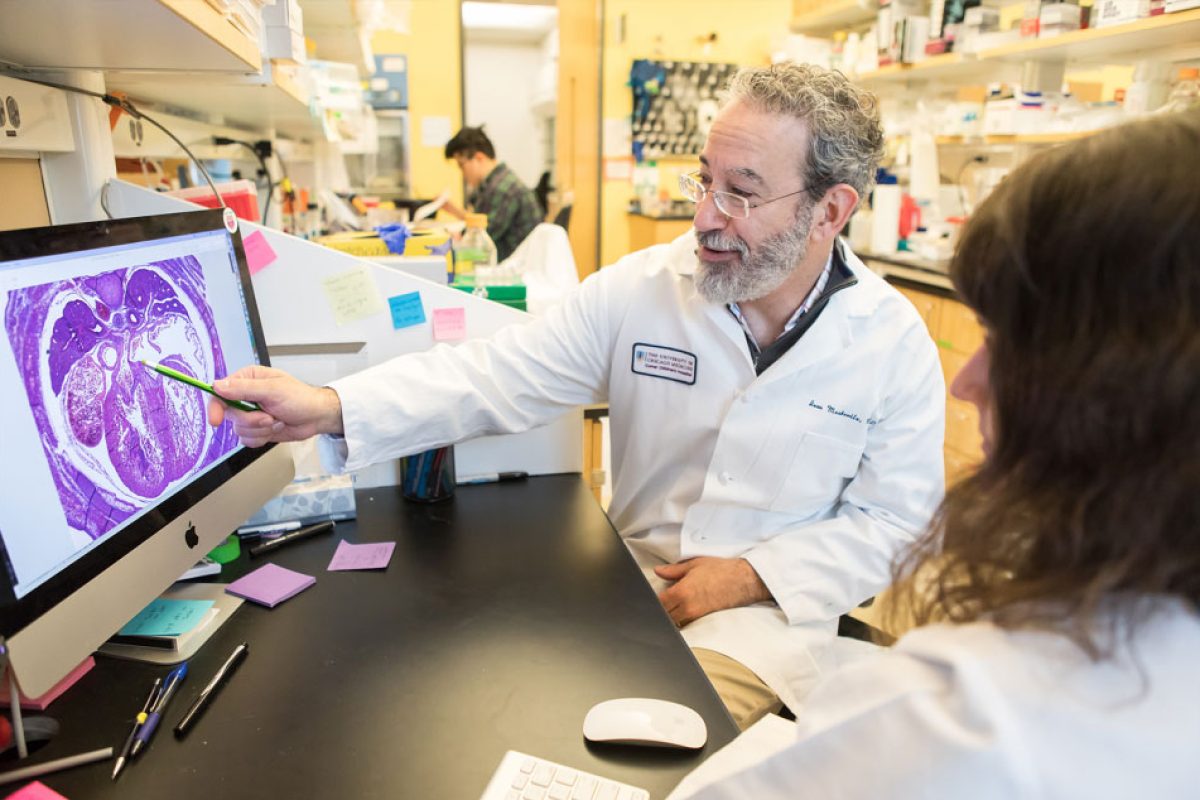

While physicians don’t always know why an infant develops CHD, the condition often runs in families, signifying a genetic cause. Ivan Moskowitz, MD, PhD, professor of pediatrics, pathology, and human genetics at the University of Chicago Medicine, is investigating the genetic causes of CHD in an effort to improve diagnosis and treatment of children born with this condition.

“We are discovering how genes and teams of genes work together within a developing heart,” Moskowitz said.

This work has been supported by a donation from The Heart of a Child Foundation, founded and managed by Rashida and Raghu Mendu. The foundation focuses on advancing research to find the causes of congenital heart defects and the care of children born with heart defects.

Moskowitz and his team are investigating signaling pathways in the heart—groups of molecules that travel from one cell to another to control what the receiving cell does during organ development. When a signaling pathway fails, it can lead to serious problems in heart development.

Moskowitz’s team is focused on the implications of a particular signaling pathway known as the “Hedgehog signaling pathway.” The Hedgehog protein was first discovered by researchers studying the fruit fly who thought that flies lacking the protein resembled a hedgehog. These researchers went on to win the Nobel Prize for their important contributions to the understanding of the genetics of early embryonic development. However, it has not been known how Hedgehog signaling controls heart development.

By studying this pathway, Moskowitz’s team seeks to understand how Hedgehog signaling affects the heart’s development. His team has observed that Hedgehog signaling controls when cells, called “cardiac progenitors,” change from young, immature cells to mature, specialized cells—a process called differentiation.

Cardiac progenitors that receive Hedgehog signaling migrate to the heart, where they contribute to the development of necessary structures and subsequently differentiate.

In the lab, when the Hedgehog protein is removed, the cardiac progenitors differentiate at an earlier stage, preventing them from supporting the heart’s development. This causes an atrioventricular septal defect, a type of CHD, in which there are holes between the chambers of the left and right sides of the heart. Surgery is required to close these holes.

“It is possible that abnormal control of differentiation timing underlies several types of CHD, or even birth defects in other organs,” Moskowitz said.

For Moskowitz, advancing the understanding of cardiac development, including the role of the Hedgehog signaling pathway and the causes of CHD, are essential for developing improved diagnosis and treatment approaches to benefit those affected by CHD. Moskowitz’s research has critical implications for the many families facing a CHD diagnosis.

If you are interested in supporting Moskowitz’s research, learn more about the Heart of a Child Giving Challenge.