Since it became formally affiliated with the University of Chicago in 1958, the Chicago Home for Incurables has contributed more than $35 million to support medical research, with an emphasis on chronic and incurable diseases. In June 2018, the Home transferred its total assets—$12.35 million—to the University of Chicago Medicine to support research related to these diseases.

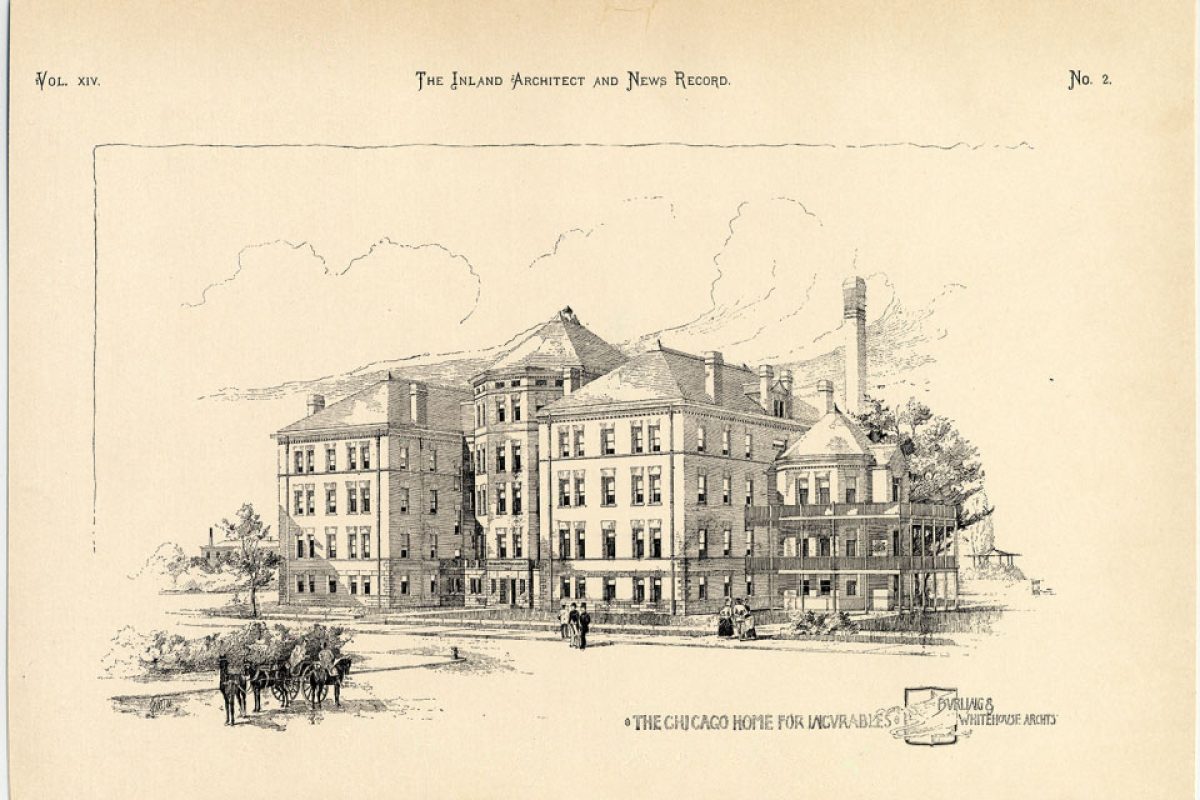

Established in 1886, the Chicago Home for Incurables has a long and storied past, which began with a $625,000 bequest from Chicago philanthropist Clarissa C. Peck. At the time, it was the largest philanthropic donation ever made by a woman in the US.

Upon Mrs. Peck’s death, her will was unsuccessfully contested by a self-proclaimed grandchild. An 1885 New York Times article luridly recounted the Peck family saga, which included denials of relationships and parentage, claims of coercion, and even accusations of murder. Despite this colorful family history, Clarissa Peck’s charity and her vision for the Chicago Home for Incurables came to fruition.

In 1898, the Home was built at 56th Street and Ellis Avenue—the location of the Young Memorial Building today—to care for individuals in Cook County with conditions that were then deemed “incurable,” including tuberculosis, rheumatism, paralysis, and locomotor ataxia (known today as tabes dorsalis).

Additional philanthropic support for the construction and expansion of the Home was provided by Marshall Field, founder of the eponymous Chicago-based department store; Daniel B. Shipman, who made his fortune in the white lead industry; and Otto Young, a merchant and real estate mogul.

The Home accommodated 125 patients, who had access to lawns with shade trees and swinging hammocks, reading rooms, and a parlor on every floor. Patients were provided with wheelchairs, and male patients could go to a smoking room to “indulge to their hearts’ content in the use of their favorite brands.”

In a 1904 Chicago Tribune article, Harlow N. Higinbotham, former president of the Home, said, “I have never known an institution where there was such a spirit of camaraderie and cheerful content as exists there. It would not be suspected in a home where the qualification for entrance itself must be the incurability of the disease. Yet, from the moment of entrance, the patient finds quiet, rest, good food, good clothing, cleanliness, and order.”

According to a 1914 article in the Daily Maroon, patients were also invited to attend athletic contests at Stagg Field free of charge, and several boasted that they had “never missed an athletic contest under favorable weather conditions.”

The search for cures

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, scientific and medical discoveries led to significant progress in our understanding of various diseases. However, the development of effective therapies lay further ahead in the future.

TUBERCULOSIS

The Chicago Home for Incurables included a 68-bed ward dedicated to caring for patients with advanced cases of tuberculosis (TB), an infectious disease that typically affects the lungs but can attack any part of the body. Occupying the south wing of the home, the TB ward was established by Otto Young.

During this time, TB was a major threat to public health in North America and Europe. In the US, the incidence of TB in 1900 was 194 cases per 100,000 (compared to 2.8 per 100,000 in 2017).

In an effort to cure the disease and curb its spread, institutions called sanatoriums sprang up, providing patients with a regimen of good nutrition and access to fresh air, then considered the best treatment available.

In 1882, Robert Koch, a German physician and microbiologist, made a groundbreaking discovery: the identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacterium that causes TB. Despite this demonstration of TB’s infectious nature, the sanatorium movement prevailed, with many continuing to believe that lifestyle factors, such as lack of fresh air, contributed to and aggravated the disease.

In the early 1900s, French bacteriologists Albert Calmette and Camille Guérin achieved the first success in developing a TB vaccine, known as the bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine. Though the vaccine remains widely used throughout the world today, a landmark 1994 study showed it to be only 50 percent effective in reducing the risk of the disease.

In the 1920s, University of Chicago researcher Alexander A. Maximow, MD, provided a new understanding of TB when he reproduced the disease in lung tissue isolated from rabbits and traced its progression under the microscope. However, it wasn’t until the 1944 discovery of streptomycin—an antibiotic used to treat bacterial infections—that a cure for TB became a reality. Subsequently, sanatoriums became obsolete, as patients with the disease no longer required multiyear periods of hospitalization.

Though treatable today, TB remains one of the top 10 causes of death worldwide, affecting nearly 10 million people annually, including half a million cases of antibiotic-resistant TB. While the rate of TB infection in the US has declined nearly 90 percent since the early 1950s, the search continues for a vaccine that fully protects against the disease.

LOCOMOTOR ATAXIA

Locomotor ataxia, known today as tabes dorsalis, is a slow degeneration of the nerve cells and fibers that carry information to the brain. The condition results from an untreated syphilis infection and affects the nerves in the dorsal columns of the spinal cord. Symptoms generally do not appear until 20 to 25 years after the initial infection and include diminished reflexes, loss of coordination, episodes of intense pain, personality changes, dementia, deafness, and visual impairment.

In 1912, Joseph Waldron Moore, MD, and Hideyo Noguchi, MD, of the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in New York (the Rockefeller University Hospital today) isolated the syphilis bacterium,establishing the disease as the cause of a condition then called “general paralysis of the insane.” Prior to this discovery, the origins of this condition eluded physicians.

By 1926, the prevalence of syphilis was as high as 35 percent among those of reproductive age. Although the 1928 discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming, MBBS, led to dramatic reductions in the incidence of the disease in the following decades, it is once again on the rise in the US.

From 2013 to 2017, there was a 73 percent increase in cases of primary and secondary syphilis and a 153 percent increase in cases of congenital syphilis, whereby the disease is transmitted from a pregnant mother to her unborn child. In 2018, the number of babies born with syphilis reached a 20-year high. In response to these rising numbers, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention called for educating physicians and nurses about symptoms, testing pregnant women considered at risk, and developing a better diagnostic test.

Paving the way for modern medicine

With scientific and medical progress came a shift in attitudes toward medical care. By the 1950s, the focus turned toward rehabilitating patients, rather than providing long-term care in facilities like the Chicago Home for Incurables.

Former Dean of the University’s Division of the Biological Sciences Lowell T. Coggeshall, MD, noted in a 1959 Chicago Tribune article: “Rehabilitation techniques developed, particularly during World War II, have completely altered the outlook for thousands of patients who would formerly have been confined to bed for the remainder of their lives.”

In response to these changing views, the Chicago Home for Incurables became formally affiliated with the University of Chicago in 1958, and subsequently contributed $1.5 million to construct a new three-story, 104-bed hospital. Named for Clarissa Peck, the Peck Pavilion was built in 1961 to care for patients with diseases considered, or formerly considered, chronic or incurable, and for research to develop better treatments and even cures. Representing a new approach to medicine, the hospital employed physical therapists, social workers, and psychiatrists tasked with rehabilitating patients. The Peck Pavilion remains part of the medical campus today.

The quest continues

Since the Chicago Home for Incurables was founded, society has benefited from significant advances in science, medicine, public health, and sanitation. From the time the Home was established until its closing in the late 1950s, the average life expectancy in the US rose from 47 to 67 years.

Despite this progress, many challenges remain, as chronic medical conditions like diabetes, heart disease, and obesity are on the rise. Today, nearly half of all Americans suffer from at least one chronic disease.

Physicians and scientists continue to advance understanding and develop new solutions to medicine’s most perplexing problems. Their recent breakthroughs at UChicago Medicine—from helping amputees learn to control a robotic arm through electrodes implanted in the brain, to performing back-to-back triple-organ transplants, to creating models that predict the spread of the flu throughout the US—would likely sound like science fiction to those who originally established the Home over a century ago.

The legacy of the Chicago Home for Incurables lives on in the pursuit of knowledge, lifesaving treatments, and, ultimately, cures. And it all started with one woman’s foresight to make a bequest that would benefit others for years to come.

Originally published in Medicine on the Midway, Spring 2019